1912

1929

12

722-722a-722b

A team of dedicated board members, volunteers, and student interns has published every page in Volume 9. This volume includes 360 images of paintings and lyrical descriptions of birds, now available online for everyone to enjoy anywhere in the world. This is a monumental task. Each volume requires approximately 400 hours to photograph, edit, transcribe, catalog, and publish online. We need your support to complete this work.

If you're tech-savvy, have a good eye, are meticulous with details, and love structured data, please consider volunteering by emailing us at hello@rexbrasher.org.

We encourage all bird lovers and supporters to consider a monetary donation to support our mission to make Rex's work available for everyone. You can provide a one-time or recurring donation online.

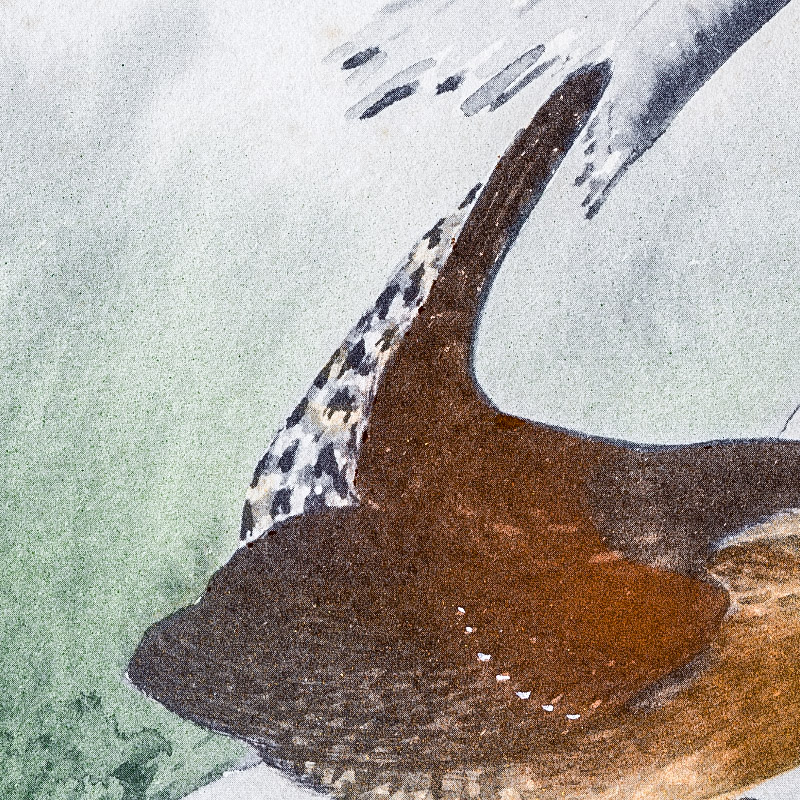

The blight which destroyed our chestnut trees brot some benefit to winter birds in its devastating course. The bark clung to the dead trunks for years and many grubs and insects hibernated beneath.

I was on the hill one November morning, "working up" next year's wood pile. The low slanting sun rays fell warmly into the sheltered nook and Otter Brook chirruped with Spring loquacity. Except when starting the nick, swinging the ax has become automatic, and lines from half forgotten poems separated from the skein of thot:

"Soon the royal splendor of November

Will wasted be, the leaves to ashes burn,

And her few lingering warblers will remember

The spell of silence and grow taciturn."

Coat followed jacket lying on a stump — smoke from the old briar drifted alee in the faint air — ax strokes returned from the cliff with but slightly diminished intensity. Between ringing blows I heard the double parted trill of a WINTER WREN. I knew from experiences in Maine lumber camps that the little brown elf followed up ax sounds so I did not stop chopping. Each repetition of "the wild, sweet melody" sounded nearer and soon the three inch music-box was burrowing into the bark of a down chestnut within six feet of me. The ax was relieved from duty then and I sat on the tree where he was dining. Presently he came to a spot of resistant bark scarcely a yard away. The strip extended to my hand. Would it scare him off if I twisted it open? Not a scare! Into the opening he dove, gobbled two fat grubs, then sat on his comical uptilted tail and thanked me with his sweet rendering of the high notes of a miniature bagpipe.

A nor'west squall swept down over Buffalo Mountain with a sudden swirl of snow gusts but my Pyxie friend and I sat it out. He sang as cheerily and hunted as busily as in the sunlit peace preceding the outburst.

Salutamus Hiemalis! Sitting there on that November day I realized that you possessed in your indomitable little heart two virtues man has sought forever — courage and the will to "play the game" in storm or sunshine.

Among "the things I do with myself in the country" is visiting the workshop and releasing any birds who have used it for sleeping or hunting. The Fall and Winter of '28 and '29 have been remarkably mild — unequaled in a half century's remembrance, and one of these birds has remained here all season. I have escorted him to the shop door three times and nearly every morning when I go on the porch for a stove log his cheery chee-chee-chee-e-e-e greets me out of the dim dawn.

I do not see him often but when he hears movement outside the house, thin call notes from a hidden nook announce his presence. "Good morning — another day — what you goin' to do with it?"

"Write about you — you silly little imp — sticking around these cold New England rocks when you could be in Miami."

NEST in stump cavities or among roots of upturned trees. Built of small twigs, plant stems, moss and lichens, closely woven and warmly lined with moss, fur, hair and feathers, leaving only a small circular entrance.

EGGS: 5 to 8, creamy white, minutely dotted with reddish brown and lavender.

Eastern United States and Canada. Breeding south (in mountains) to Massachusetts, New York, Michigan and Wisconsin; rarely to northern Indiana, Illinois and central Iowa and thru higher altitudes of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia to western North Carolina. Winters from southern breeding limit to northern Florida and along Gulf coast to Texas.

On seaward shoulders of the Cascades, looking down on Puget Sound, there are reaches of virgin forests which have never been logged or touched by fire. For centuries seawinds have loaded them with moisture — the long days of Northern summers have filled their dim recesses with a tropic growth of fern, vine, maple and briar. There are mountain torrents and quiet pools where rainbow trout play undisturbed. There are vistas from some folds in the hills which end with distant seashine westward and of snows to the north which never melt. There in the dim forest paths between impenetrable jungles of moss covered fallen tree-paths as old as the great firs, the WESTERN WINTER WRENS live and sing. —Churchill.

Western North America. Breeds from Prince William Sound, Alaska and western Alberta south to central California and northern Colorado. Winters in southern British Columbia, south to southern California and southern New Mexico.

Kadiak Island, Alaska.

A tree up to 50 feet high, distributed on river banks and moist locations in California, Oregon, Washington and southern British Columbia.